Remembering John Rogers

The following are excerpts from a live KMUD-FM radio show on Oct. 20, 2021 that honored the legacy of John Rogers, a cofounder and former Executive Director of Institute for Sustainable Forestry.

Gray Shaw: Welcome back to The Institute for Sustainable Forestry’s Sustainable Forestry Journalism Project. I’m your host, Gray Shaw. Recently the Institute lost one of its early leaders, John Rogers. For the next half hour, we’re holding a live discussion about where ISF came from and where it’s going in terms of John’s legacy…Now, I’m handing over the reins to some people who knew John well.

Jeff Hedin: I met John in the mid-’90s, and if there’s someone who wants to start off with how important he’s been to us all since earlier times, please do. Some of you knew John from the days that ISF was being conceived. Some of you probably were sitting at that table as the Ten Elements of Sustainability were being offered and agreed upon, and my introduction to John came a few years later.

Richard Gienger: John has been a stalwart part of the Southern Humboldt/Northern Mendocino communities and part of a number of villages. It takes a village. John was part of many villages, and many people have been close with John over the years in all kinds of circumstances. And John was a serious woodworker and got all motivated by a number of things relative to the environment, especially sustainable forestry.

Douglas Fir: John was a deep thinker, and I look around our community and I see that we’re losing our public intellectuals. And I put John in that category because he was kind of a focused public intellectual in the sense that his field was wood and forest, and he was a nerd in that respect. He was a numbers guy, and one of the few people who really approached the situation in our forests and in our communities and the relationship between the two in a really empirical way. And he was recognized across the industry for being that kind of person, being the forestry nerd.

Dave Kahan: [John] churned out these voluminous reports that absolutely blew my mind. I’m happy to say that I didn’t have to read them because I’m not as much of a nerd as he was about that kind of stuff, but I was really impressed with his work ethic and his ability to teach himself what he needed to know in order to turn out that product, and he always kept up a jovial attitude.

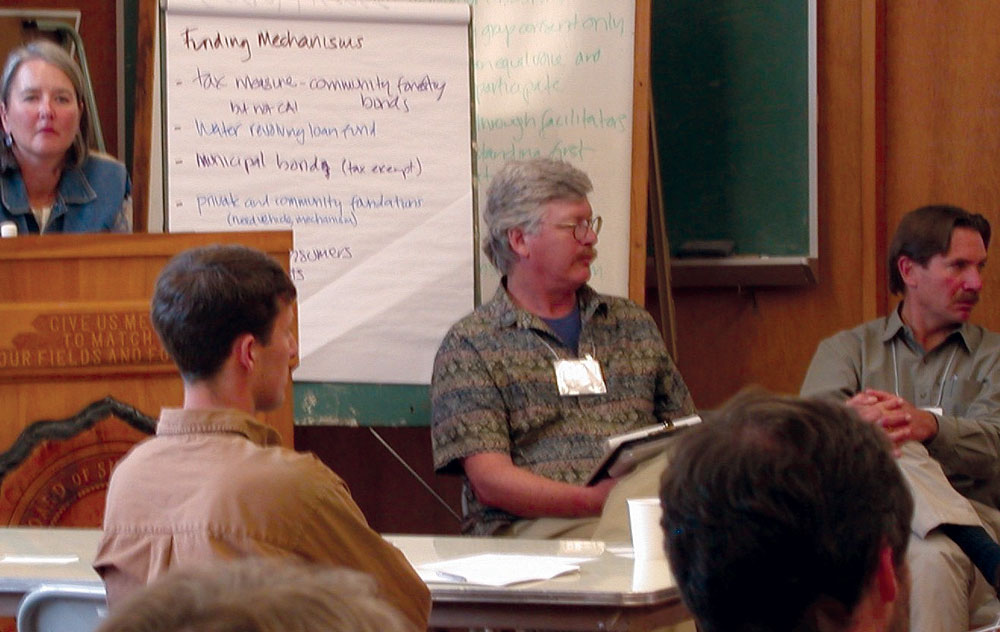

I met him first as a colleague in the formation of ISF, which was an incredibly magical weekend of something like 60 or 80 people packed into Jan [pronounced YAN] Iris’s place at Hokahey and…it was one of the most incredible weekends I ever spent. It was so inspiring to have that many people travel as far as they did from pretty much all over the Northwest and from such different walks of life, and out of that came the Institute. And then in the course of becoming a colleague, we became friends, which is hard not to do.

Douglas Fir: I want to refer to something Dave [Kahan] said because I think it’s really important, and that was the jovialness, and I wouldn’t actually characterize it as jovialness. I would characterize it as a strong sense of irony, and that sense of irony on the part of John always created a sense of the absurdity of the world. And he always got a kick out of that, a humorous kick out of that. And it was always a twinkle in his eye around what was going on, because he always saw it through his ironic lens.

The Ten Elements of Sustainability

- Forest practices will protect, maintain and/or restore the aesthetics, vitality, structure, and functioning of the natural processes, including fire, of the forest ecosystem and its components at all landscape and time scales.

- Forest practices will protect, maintain and/or restore surface and groundwater quality and quantity, including aquatic and riparian habitat.

- Forest practices will protect, maintain and/or restore natural processes of soil fertility, productivity and stability.

- Forest practices will protect, maintain and/or restore a natural balance and diversity of native species of the area, including flora, fauna, fungi and microbes, for purposes of the long-term health of ecosystems.

- Forest practices will encourage a natural regeneration of native species to protect valuable native gene pools.

- Forest practices will not include the use of artificial chemical fertilizers or synthetic chemical pesticides.

- Forest practitioners will address the need for local employment and community well-being and will respect workers’ rights, including occupational safety, fair compensation, and the right of workers to collectively bargain, and will promote worker owned and operated organizations.

- Sites of archaeological, cultural and historical significance will be protected and will receive special consideration.

- Forest practices executed under a certified Forest Management Plan will be of the appropriate size, scale, time frame, and technology for the parcel, and adopt the appropriate monitoring program, not only in order to avoid negative cumulative impacts, but also to promote beneficial cumulative effects on the forest.

- Ancient forests will be subject to a moratorium on commercial logging during which time the Institute will participate in research on the ramifications of management in these areas.

We lost another of what I call the great people of Southern Humboldt, clearly. One thing I’ve noted over the years is that different people step up for different things, and sometimes it’s surprising, like people who have not been seen to exhibit an activist side will suddenly come out and do something really activist. And I think of John in that respect, because John was never part of the Acorn Alliance that did direct action against nuclear establishment, both in weapons and power. But John went to Seattle [for the demonstrations against the WTO] and that really changed him as well. He was on the streets in Seattle in 1999, and that was his expression of a kind of activism that came out of a lot of deep thinking about the economy and about globalization, and he took that on in the way that he took everything on, out of a deep sense of both conviction and understanding.

Jeff Hedin: John brought to my conversational realm the best contextualization of what we were doing here in terms of what was going on in the rest of the entire planet’s human community than anyone else I was talking with.

Bill Eastwood: I would like to emphasize the practical nature of John. We were trying to build a hardwood mill in Piercy, which involved a million things, and John kinda dove into a lot of them. Picking out the mill, finding out about grading trees, grading lumber, grading logs… There were a million details to think about, like drying schedules—he dove into that one, too.

all photos this article by Kathryn Lobato

Tracy Katelman: The first time I met John was during Redwood Summer [1990], and I remember there was a meeting up at the Action Center—the only third-floor place in Garberville—to talk about how to go beyond Forests Forever and create what eventually became the 10 Elements. I think it was in the fall when we did that meeting at Jan and Peggy’s, but this was in the summer, in the midst of all the chaos that went on. And what I remember first about John was that he came to the conversation as a woodworker because he loved the wood and he got it about the wood, and that really hit me at the time because I’d been working on the Forest Stewardship Council, the international stuff. And that started through the Woodworkers Alliance for Rainforest Protection. So I immediately made that connection and started listening to John and how he came from that place of heart and love and appreciation for that sensuousness of the wood.

And in the early days, we were focused on all the different hardwoods, the madrone and the tanoak and the bay. And John knew about them from that place of working with them. John and Bill [Eastwood] and Jan [Iris] and all the folks that were living in the neighborhood all brought their own different experience to it, and he (John) was super welcoming to me as somebody who came in new to the community. And then what I watched him do over the years, kind of following up on what Bill and Dave and others have said, is that we’d come up to a spot beyond what we knew– we were all these visionaries and had all these great ideas about how we’re gonna change forestry in California and all this–but we’d come up to some kind of roadblock, and then John would dive in and figure it out. So first, in those days it was forestry policy, and then later it was how do you run a mill? And then it was the conversations about the economics, about the PL takeover, and always it was John who went in and did that deep dive and figured out the details so the rest of us could continue pushing it forward..

Douglas Fir: Well, Tracy, I want to thank you for, in one of your emails, closing with “step-by-step,” and I think it was picked up by Dave Kahan because that was the classic John closure as you departed after a fierce policy argument or discussion. He would say, he’d kind of tilt his head and go, “Step-by-step.”

THIS PLACE THAT YOU BELONG TO

By Wendell Berry

It is hard to have hope. It is harder as you grow old,

for hope must not depend on feeling good

and there is the dream of loneliness at absolute midnight.

You also have withdrawn belief in the present reality

of the future, which surely will surprise us,

and hope is harder when it cannot come by prediction

any more than by wishing. But stop dithering.

The young ask the old to hope. What will you tell them?

Tell them at least what you say to yourself.

Because we have not made our lives to fit

our places, the forests are ruined, the fields eroded,

the streams polluted, the mountains overturned. Hope

then to belong to your place by your own knowledge

of what it is that no other place is, and by

your caring for it as you care for no other place, this

place that you belong to though it is not yours,

for it was from the beginning and will be to the end.

Belong to your place by knowledge of the others who are

your neighbors in it: the old man, sick and poor,

who comes like a heron to fish in the creek,

and the fish in the creek, and the heron who manlike

fishes for the fish in the creek, and the birds who sing

in the trees in the silence of the fisherman

and the heron, and the trees that keep the land

they stand upon as we too must keep it, or die.

This knowledge cannot be taken from you by power

or by wealth. It will stop your ears to the powerful

when they ask for your faith, and to the wealthy

when they ask for your land and your work.

Answer with knowledge of the others who are here

and how to be here with them. By this knowledge

make the sense you need to make. By it stand

in the dignity of good sense, whatever may follow.

Speak to your fellow humans as your place

has taught you to speak, as it has spoken to you.

Speak its dialect as your old compatriots spoke it

before they had heard a radio. Speak

publicly what cannot be taught or learned in public.

Listen privately, silently to the voices that rise up

from the pages of books and from your own heart.

Be still and listen to the voices that belong

to the streambanks and the trees and the open fields.

There are songs and sayings that belong to this place,

by which it speaks for itself and no other.

Found your hope, then, on the ground under your feet.

Your hope of Heaven, let it rest on the ground

underfoot. Be it lighted by the light that falls

freely upon it after the darkness of the nights

and the darkness of our ignorance and madness.

Let it be lighted also by the light that is within you,

which is the light of imagination. By it you see

the likeness of people in other places to yourself

in your place. It lights invariably the need for care

toward other people, other creatures, in other places

as you would ask them for care toward your place and you.

No place at last is better than the world. The world

is no better than its places. Its places at last

are no better than their people while their people

continue in them. When the people make

dark the light within them, the world darkens.

From This Day: New & Collected Sabbath Poems

(Counterpoint, 2013)

Richard Gienger: He did that after every Redwood Forest Foundation (RFFI) meeting, that’s for sure.

John was all the time preaching in all kinds of ways that the forest needs to grow and to be valuable over time… And another principle that is so important to not go away was his “I know that some foresters think a little bit of herbicide will save you a lot of herbicide later.” But John was really opposed to the use of any herbicides, right down to the concern, directly, about the health of his grandchildren. And also John was so dedicated to community involvement, not this pecking order or whatever you want to call it, of the “masters that make the rules for the wise men and the fools,” but to actually integrate communities in the day-to-day relationship with the forest and working toward these principles.

Seth Zuckerman: Thanks for having me and for letting me know about this [on-air memorial]. John—what an amazing presence in the world of wood in SoHum. I just want to say how steadfast he always seemed…. Circumstances could buffet the different things that we were trying to do, and he was just such a stalwart, undeterred, and I’ll just leave it at that. I’ve really been enjoying hearing everyone’s stories about him.

David Simpson: And I’d like to toss in that, in a very real way, the fact that everybody I know who’s on this phone conversation over the air stems from John’s presence when I needed a little advice, and you’re all treasures to me. I value every one of you, and I think that John probably brought many of you guys together, as well as bringing all of you into my life. And I think that role he had and his being in so many different conversations during his time here was a very important aspect and reminds me that the idea of sustainable forestry is not something that can be accomplished by one person alone. It does take this conversational milieu, and John said it very well.

Dave Kahan: And speaking of bringing us all together, this is slightly tangential, but I referenced earlier what we call the brainstorming weekend that resulted in the creation of ISF, and one of the remarkable aspects of that for me was witnessing Seth and Tracy co-facilitate that gathering. That in itself was pretty mind-blowing.

[chuckles and agreement]

David Simpson: They could turn those big pages. [chuckle] And they could get it written down, too. John as an individual personified that in the whole community. He manifested community in his relationships. And his happiness was interacting with people, whether it was playing poker or going to concerts. The music, like really incredible—we haven’t even delved into that aspect… All this will happen at the memorial this spring, and I would encourage everybody who hasn’t to look at the incredibly beautiful moving obituary that his family put together that’s on Redheaded Blackbelt’s site. [search kymkemp.com, John William Rogers]

Bill Eastwood: And speaking of community, he and Kathryn threw a pretty good solstice party too, every year for a while.

Dave Kahan: Not to mention that every Friday cocktail party kind of deal at their place in Redway for many years. And I’ve seen that he loved his children and grandchildren, was very connected, and it’s a shame that he passed so quickly. And we need people to step up and do what they can to try and cover the ground that he did.

Richard Gienger: And not to be intimidated by the size of his contribution. We need everybody on board.