Pomo Perspective: Priscilla Hunter and Polly Girvin on Jackson Demonstration State Forest Logging

Transcript of April 19, 2021,

KZYX Public Affairs show hosted

by Alicia Littletree Bales

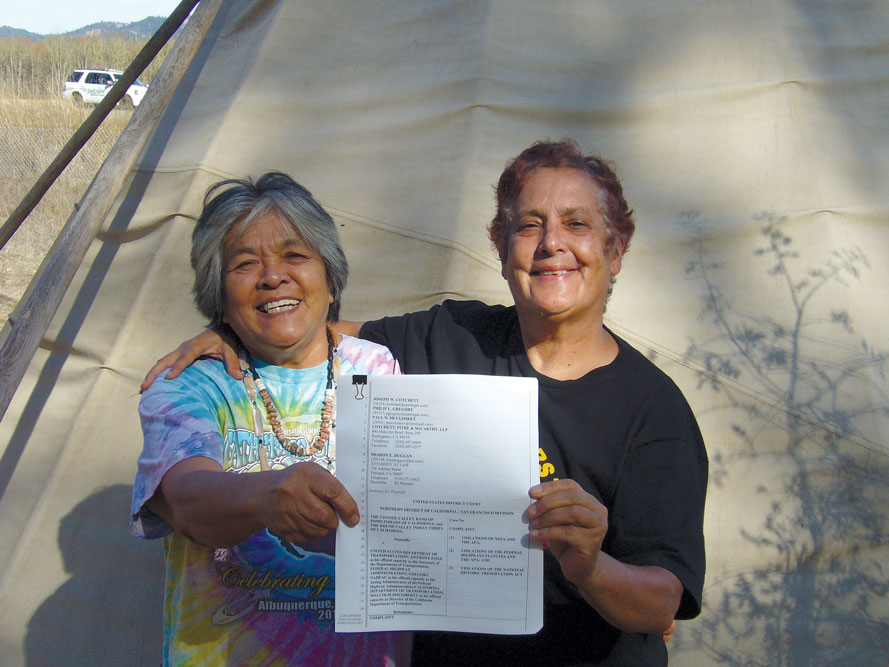

Alicia Littletree Bales: [Following radio show’s intro music] That was Holly Near and Emma’s Revolution performing “Listen to the Voices.” I’m Alicia in the Ukiah studio, and I’m here with Priscilla Hunter, who’s an elder and former Chairwoman of the Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians, Chair of the Sinkyone Tribal Wilderness Council, and Polly Girvin, human rights attorney and long-time environmental and Indigenous rights activist. They’re both founding members of PAIEA, which is the Pacific Alliance for Indigenous and Environmental Action, and members of the SEIJ affinity group. (Social Environmental Indigenous Justice) We’re going to be talking about Coyote Valley’s opposition to logging plans proposed in ancestral Northern Pomo and coast Yuki territory that’s now called Jackson Demonstration State Forest.

Cal Fire has half a dozen proposed plans to log in the redwoods there, and at least one is approved and ready to start operations. Last week, tree sitters climbed up two of the largest trees in the cut area, and the Mendocino Trail Stewards have been organizing to bring attention to the plans for months. Coyote Valley recently requested government-to-government consultation with the state of California to discuss the logging. So Priscilla, welcome. Polly, welcome. I’m turning it over to you.

Priscilla Hunter: Thank you. Such a beautiful song. Every time I listen to it, I hear more what the words are. Well, I’m honored to be here. And first of all, be thankful for ancestors, and Mendocino was a real tough struggle for our ancestors, and I’m really thankful for them to be able to survive because they knew how to take care of, this land, and lived on what was here. And didn’t go out and cut every tree down they can see to make some money. You know, going up to the [Jackson Demonstration] state forest, I couldn’t believe what I saw. People were telling me that they were cutting there, and I was like, No, that must not be it, because it’s state forest, right? So I always thought it was all protected. So then I went up and saw total destruction of the trees, and the scattered trees that were left over, and learned about how many cultural sites they were destroying. You know, our ancestors and people ran up to get away from being killed, raped, kids taken away from them, slaughtered, really slaughtered. Slaughtered. And then they ran up in the mountains and the thing is, they went over to the ocean too, traveled there, lived there. They lived there, and sometimes brought fear, thinking they were gonna be raided or attacked at any moment….And you think that’s not gonna happen—but yet it continues. They’re attacking our ancestors… When I went up there [Jackson State Forest], I can feel the spirit, a cry of our ancestors. I’m telling you, you could feel that. And it’s very disturbing, very disturbing. And they put the village sites as a small place [on their maps], we only went 100 feet or whatever? We went all over those places. Our ancestors traveled all over, and they [state officials] are like, ‘Well, we can only go this far, that’s how far the site went.’ I’m like, Heck No. That whole place is a village site, cultural site. The whole place. And they put the roads in, kill all the animals. Kill all the trees. All the fish, water. Who cares? I want that wood. I want that tree.

You know, it’s a state forest. That means it’s the people’s forest. That doesn’t just mean the loggers’ forest for cutting… We want to preserve it, put it in a reserve and have a moratorium at this time, with no cutting until we have a time to do our studies or research to prove to the Governor. We have to call in the Governor, we can’t go to Cal Fire. I think there’s a little conflict there, I would say. We want to do it gracefully and carefully because we’re working for the protection of our ancestors and believe it’s a sacred place, and so we have to do it spiritually and…in a good way. But a lot of times it makes you very angry, very angry. As an Indian person, I get very angry at times. I’m not saying I don’t, because the history is repeating itself with the Indians still. We need to return for all our artifacts, get cultural things back and all of our burial sites and even…the remains that are in museums. And until that’s all complete and done with, this world will not be good. That’s what I believe. And that’s what the disturbance is [that’s] happening too. I believe that the Spirit is unrest, and we have a hard struggle with the whole world….This one cousin of mine in Tennessee told me that they had this dream catcher, and this one guy had an Indian scalp in the middle of it, yes. I was like, What? Things like that, the [Native American] Heritage Commission I would like to see become strong here….

We want to preserve the whole [Jackson State Forest], over 40,000 acres, and have a moratorium on this [logging] until we can work this all out. That is one of our main objectives, and it’s a top priority. So there you have it.

Alicia Littletree Bales: Alright, that was Priscilla Hunter. She’s the former Chairwoman of the Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians, and currently the Chair of the Sinkyone InterTribal Wilderness Council. And now, Polly Girvin is here to talk more about the government-to-government consultation and Jackson State Forest.

Polly Girvin: I’d like to first say that it’s my great honor to work with the Coyote Valley band of Pomo Indians, a tribe that, since I have known them, has historically taken the courage to stand for their sovereignty to the fullest extent possible. So what we’re involved in here, and why we have a special avenue of being able to compel the state to listen to our concerns, is that there are executive orders both at the federal and state level that acknowledge the sovereignty of tribes, acknowledge the tribes are nations within a nation, going all the way back to the Worcester vs. Georgia seminal case in the Supreme Court that determined that Indian nations are distinct political communities. They’re not just…minority-status citizens, but indeed nations….

Thirty years ago, we were advocating for the government-to-government consultation process between state and federal governments and tribes. We encountered Ronald Reagan’s resistance—he wanted to put all funding to tribes through state block grants. We resisted at the national level and said no. Under the Constitution, treaties, and executive orders, we have a status higher than states and must be dealt with accordingly.

It often takes a while for policy arguments to be implemented, but Coyote Valley is currently at the table in five government-to-government consultations to protect the environment, to protect their cultural resources and their artifacts. At the state level, more and more tribes are beginning to utilize this mechanism. So we are happy to be amongst that group, because remember the dishonor of the State of California and the federal government and how they negotiated with Indians historically. There were good-faith trade negotiations in both Hopland and in Lake County, Scotts Valley. The Indians were in those good-faith negotiations, were promised all of the acreage around Clear Lake for the extinction of their Aboriginal title up here. But of course, those treaties were never honored.

The State of California in the gold rush years (when people thought gold was everywhere) objected to treaties, and they were hidden under seal for 50 years. So this is the history, a long legacy of dishonor at the state level, that this executive order that we’re now currently operating under was a part of trying to rectify the past terrible dealings between the state and tribes. So this is the mechanism we’re using. We are not just negotiating with CalFire, we’re not consulting with Mike Powers, forest manager. We are discussing with the top brass of every agency that’s directed towards protecting our cultural resources, which includes CalFire, which includes the State Office of Historic Preservation, which includes the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

This is a consultation between an Indian nation, Coyote Valley, and the State of California. We in these proceedings will be looking at a host of issues. As Priscilla said, our top priority is to protect the trees, and we are. As members of PAIEA, we kept the word “Action” in the description of our organization because we do support and respect non-violent direct action where necessary to protect Mother Earth.

So we are very happy the tree sitters went up, and to quote Priscilla’s great-granddaughter, my beloved Courtney, when she was asked by her cousin, “Well, what is a tree sitter?” she goes, “They’re babysitters for the trees.”

We hope to train our children in our tribe that we do listen to the ancestors cry, we never turn away. And that we hope to heal in what we’re doing. It’s a big undertaking, but in all sincerity, we are trying to create a historical rebalancing because at the same time Priscilla’s ancestors were being slaughtered up here, so too were the old redwoods being ravaged. We have so few old redwoods left in this region, maybe like 3%, just like 80% of the local Indians were eradicated by disease and state-sanctioned genocide. So I call these local tribes the remnant survivors of a state-sanctioned genocide—just like the ancient trees, the few left are the remnant survivors of the brutality of the logging industry up here—and we will be looking clearly at the history of this park. We’ll be looking at their alleged studies—they keep on saying they’re studying forestry by cutting down these trees. They are alleging the clearcuts are scientific research! Well, we just have a different world view. And I hope that the state will listen to us and will know that we’re doing this in a sincere fashion, and that Priscilla feels compelled to do this to balance, to heal for the ancestors, for the forest, and for the future generation of Indian children.

It’s a sacred place out there, and they’re actually sacred sites. They have been trashed by road building, slash debris going off the side of roads. We will be emphasizing restoration and conservation…and meeting the 30 times 30 standard that the Governor has articulated for carbon sequestration purposes. These old trees are greatly necessary in the climate change struggle that we’re facing. So we’re there for the environment, we’re there for our ancestors, and we’re there for the children, and we want to thank the environmental movement, particularly EPIC, the Environmental Protection Information Center, Matt Simmons and Tom Wheeler, who have been very helpful and collaborative with the Tribe. They are our regional experts on the Forest Practice Act. We go back a long way with them, all the way to the EPIC vs. Johnson decision, where the Indian Treaty Council, of which Priscilla was on the board, and Sharon Duggan litigated. You can’t just go timber harvest plan by timber harvest plan, you have to involve the whole watershed in your analysis—it’s called a cumulative impact now. It was a completely important case, and I’m proud to say that Priscilla was involved in that one too. So we have a long history of collaborating with the environmental movement, and we are continuing with great respect for the tree sitters, for the environmental lawyers, for the [Mendocino] Trail Stewards association.

We hope to keep a strong united front, and that is, we are joining all the forest defenders of Mendocino County. It’s a long history, and we said, “No Compromise in Defense of Mother Earth.” And we proudly have lived our lives under that slogan and motivation, and it’s just lovely. Circles of life—you know how we all reconnect.

Alicia Littletree Bales: Well, thank you. Can you talk about the cultural sites out there and what is known about the traditional uses of Jackson State and the relationship that Pomo people and other Northern Tribes had and have with the place?

Polly Girvin: Well, we can definitely say that there’s ancient trails that were used by Priscilla’s ancestors for thousands upon thousands of years. The ridge runners ran those ridges. And there are sites on the [Betts Report* of] 1999—they had to inventory the sites, they came up with 22. I’m sure there’s been more discovered by bulldozer since then. They have failed to do the work they were required to do under state law; they were made to do an inventory of our sites, but then they were supposed to take proactive measures to protect them, which includes having them listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the California Register of Heritage Places, which gives them an enhanced protection level. Even their very study they commissioned to say, What should we do now? They never did the follow-up work, so there’s a lot of work we have to do under federal and state law to get these places further protected.

I would say, basically, the treatment of the ancestral sites has been destruction. They in their own commission study admit that most of them have been seriously impacted by road building and debris being shoved over onto them; and in that commission study (it’s called the Betts Report of 1999), the state commissioned it, and the people who did the field surveys recommended that a road study be made, particularly in reference to the protection of the ancestral sites. They had to come up with modifications in road building, laying some roads to rest to protect the sites.

We will find out in government-to-government consultation, but my idea is they did nothing. So basically the inventory—and that’s all that I can see—was done by the state with no follow-through. So we feel that to mitigate and to heal this, they better come forward with some really helpful solutions on protecting our sites because they have been derelict in their duties, and those duties do include the protection of Native American cultural resources. And maybe they’re not as obvious as a building in DC that they’re arguing for—this is an entire landscape of sites—and under the National Historic Preservation Act, also under state law, archeological sites can be deemed districts, entire districts, not just one site by one site. We’re arguing that Jackson Demonstration State Forest is an archaeological district, and that as mitigation for the ravaging of the forest and of the sites, I think ongoing years of destruction of sites under bulldozers, they must heed our concerns. We were not at the table. The tribes here were struggling to restore themselves after illegal termination when all these laws—pro-timber industry, pro-archeologists—were being crafted. This may be one of the few times, at least locally, where we’re at the table saying, “We’re here, we want some policy changes, we want some amendments to the Forest Practice Act, and we intend to get them.”

For more information: sinkyone.org