Endangered Coho Salmon Finally Secure Habitat Protection in Marin County, CA

Two Decades, Multiple Lawsuits, and Creative Grassroots Persistence Was the Key to Success

By Todd Steiner, Salmon Protection And Watershed Network

Forest Knolls, CA—This is a story that begs to begin with the proverbial “once upon a time,” as it has all the classic elements of a captivating, decades-long tale. The endangered coho salmon is a keystone species of the Lagunitas and San Geronimo Creek watersheds, swimming 20 miles upstream each winter to spawn in natal creeks in the San Geronimo Valley, the county’s most important undammed headwaters for coho salmon. Here, the last 10% of the historic salmon run lay their eggs to regenerate the population. Sadly, redwood trees—which improve water quality, protect creekbanks, support healthy salmon, and sequester climate-changing carbon—have been reduced to just 5% of their range and are listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The plights of the charismatic salmon and the iconic redwood are a stark illustration of the impact of historically poor protection of watershed habitats.

The Recent Victory: A Stream Conservation Ordinance

In July 2022, the Salmon Protection And Watershed Network (SPAWN, a program of Turtle Island Restoration Network), compelled Marin County Supervisors to finally pass a science-based Stream Conservation Ordinance. It’s a vital victory in SPAWN’s comprehensive strategy to protect and restore the coho population of the 100-square-mile Lagunitas Creek watershed, providing a much-needed boost to efforts to eventually obtain a happily-ever-after ending.

Once numbering about 5,000 returning spawning adults annually, the current Lagunitas Creek coho population averages about 500, with a low of 52 fish in 2008–09. Over the course of this battle, Central California coho went from a threatened to endangered listing under the Endangered Species Act. The current federal Recovery Plan sets a recovery target of 1,300 redds (nests) or about 2,600 adults.

The local causes of decline mirror the issues found throughout the coho’s range: loss and degradation of habitat from ranching, deforestation, and urbanization causing incised waterways, loss of floodplains, poor water quality, and increased stream velocities from runoff from impervious roads and houses. In a nutshell, 200 years of poor land-use decisions drove the local salmon population to the brink of extinction.

Despite alarming scientific data that the population was continuing its downhill spiral, lobbying of County Supervisors that began in the early 2000s fell on deaf ears, while approved housing continued to sprawl along streambanks.

A 20-Year Grassroots and Legal Battle

In April 2003, SPAWN filed suit in Marin Superior Court against the County of Marin, which had just approved a 4,400-ft2 single-family home adjacent to important spawning habitat. With the help of attorney Michael Graf, SPAWN argued that the County illegally exempted the project from the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), approving one house at a time without considering the “cumulative” impacts of past and future development as required by CEQA. In November, the Court agreed and placed an injunction on further creekside development until a Stream Conservation Ordinance was enacted.

An important legal precedent was set—declaring that single-family homes, normally exempt from CEQA review, were not exempt when proposed in “sensitive habitats” such as creekside and wetland habitat. (SPAWN is delighted to report nearly 20 years later that it is now working with the current property owners to restore and improve habitat.)

The County appealed the judge’s decision to enjoin any future development, and while the Appeals Court upheld the failure of proper environmental review, it ruled that the lower court overstepped its authority when it issued an order stopping development until the County passed a Streamside Conservation Ordinance to clarify creekside development rules for landowners and salmon protection. The County went back to approving development, which was met by new and successful legal challenges by SPAWN. This situation was unsustainable, time-consuming, and expensive for everyone.

A Long Time Coming: Perseverance Pays Off

This story is more than a historical legal account—it is a real-world tale of perseverance, community, and inspiration.

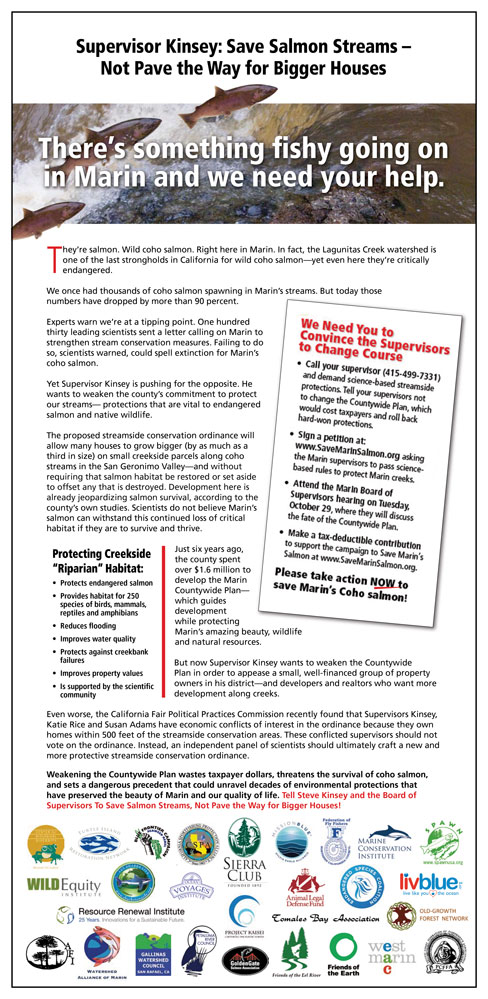

Keep in mind that intricately woven between each and every legal action presented here was a series of concerted grassroots maneuvers designed to organize and mobilize resistance to the powerful influence of the real estate industry and “property rights” extremists. These maneuvers included running full-page ads that highlighted the community of scientists and civil organizations, organizing a coalition of 30 community and environmental organizations to testify at public hearings, launching a “virtual” banner projected on the iconic Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Marin Civic Center—making headlines with the help of the San Francisco Projector Department, creating a photo-petition garnering the support of more than 5,000 Marin residents and people beyond the Bay Area, and instilling steadfast passion in everyone who cares about a future for the endangered salmon.

all graphics this article courtesy SPAWN

In 2007, the County released its draft County Wide Plan, allowing more creekside development than scientists believed the salmon could withstand. SPAWN again challenged the adequacy of CEQA analysis and the County’s proposed mitigation—the passage of a still-undefined ordinance at some vague time in the future.

Recognizing SPAWN’s past successful legal challenges and the hundreds of thousands of dollars the County was expending on attorneys’ fees, the County agreed to “toll the statute of limitations” on filing the suit to allow time for negotiations to reach settlement and avoid more losses in court. A two-year moratorium on development was approved while a “Salmon Enhancement Plan” and “Current Conditions Report” were completed by mutually agreed-upon scientific consultants.

Countering Powerful Development Interests

Once reports were completed, the County set out to develop an ordinance that would keep Marin’s real estate lobby and property rights devotees happy and somehow meet the legal requirements to protect salmon habitat.

Not surprisingly, they failed.

In September 2010, with no meaningful action to protect salmon habitat in sight, SPAWN and the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) filed the long-delayed lawsuit challenging the sufficiency of the EIR. One year later, SPAWN filed an amended petition adding a cause of action challenging the County’s failure to adopt a Stream Conservation Ordinance within the time frame prescribed as a mitigation measure in the 2007 County Wide Plan.

The County did float draft regulations that always favored development over endangered species. For example, in 2013 the County actually passed an ordinance that provided little protection for salmon habitat. While it purported to include a 100-foot creek setback rule, the fine print concealed so many exceptions and exemptions that it impacted very few parcels. It also included a “poison pill” provision that made the ordinance null if it was challenged in court, trying to place blame on SPAWN for killing it if challenged. SPAWN and CBD called their bluff and the ordinance was immediately annulled.

In 2014, the Courts again ruled in SPAWN’s favor, ordering the County to do more environmental analysis and complete a Supplemental Environmental Impact Report (SEIR), costing the County another $300,000.

Continuing to drag their feet, in 2019 the County finally released a newSEIR, which found significant impacts from new development but said the impacts could be mitigated: primarily by the adoption of a new science-based Streamside Conservation Area Ordinance—exactly what SPAWN asked for 15 years earlier.

Failing to learn from its past, the County, illegally, did not spell out what the “expanded” ordinance would include, making it impossible to know if it actually could mitigate future development; and furthermore, the County illegally granted itself another five years to write and implement it, unless it unilaterally decided it would need more than five years.

In response, SPAWN and CBD filed another lawsuit challenging the inadequacy of the new SEIR. Facing yet more expensive litigation, and with virtually no chance of successfully defending these illegal deficiencies, the County accepted SPAWN’s final offer to re-enter settlement discussions. Having squandered over $1 million on additional studies and attorney fees and facing another expensive and embarrassing defeat in Court, the County and its counsel seemed to undergo a sea change in attitude as negotiations began.

Salmon Habitat Protection Finally in Place

In July 2022 the County at last passed a science-based Stream Conservation Ordinance that protected salmon habitat and provided adequate enforcement methods including:

- 35-foot “no exception” streamside and ephemeral stream development setback

- 100-foot streamside development setback for tiny parcels with no other options limited to 300 ft, and requiring 2 to 1 native plant replacement

- Anonymous complaint system and strengthened enforcement

- Voluntary county inspection for compliance prior to sale at the request of property owners

- Requirement of a permit and site assessment before clearing vegetation or making any alteration within the 100-foot setback

- Creation of any impervious area within the 100-ft setback is subject to permit review and mitigation.

THE END or rather A New Beginning

As with any fairytale, there are elements that must comprise the story: the moral lesson, enduring characters, magic, obstacles, and happily ever after. With the grassroots magic of thousands of passionate individuals, great obstacles have been overcome to brighten the future for coho salmon on the central coast. But the ultimate ending has yet to be penned, as more work is needed to restore this once-thriving population. SPAWN, the community, and all of us as watershed stewards will continue to strive for that (once-)endangered-species happy ending we and they deserve.

For more information: https://seaturtles.org/our-work/our-programs/salmon/