From Roy’s Dam to Roy’s Riffles: Removing the Top-Priority Barrier for Central California Coho Salmon

By Rebekah Staub and Todd Steiner, Salmon Protection And Watershed Network

A free-flowing creek replaced a nearly 100-year-old dam in Central California this past year, thanks to a decades-long restoration effort that is intimately tied to the genesis of the Marin County-based Salmon Protection And Watershed Network, or SPAWN.

In December 1996, Todd Steiner stopped to look at an old fish ladder on the San Geronimo Valley Golf Course in West Marin County. The concrete fish ladder was constructed in the 1960s to allow salmon passage around the old dam that had been erected pre-golf, when the land was Roy’s Ranch. The dam was presumably built to hold water for cattle.

To Steiner’s surprise the dam’s apron had collapsed, causing migrating salmon to forgo the fish ladder and shimmy onto the concrete platform where they slammed into the dam—only to fall back and try again and again.

Steiner produced a media advisory and faxed it to local TV stations. Before noon, all four stations and CNN were filming the salmon becoming stuck on the dam’s broken apron. The footage was splashed across living rooms throughout the San Francisco Bay Area and around the world that evening. Concerned for the plight of the salmon, Steiner also contacted the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) requesting an emergency permit to net the fish and move them above the dam so they could continue swimming upstream on their spawning migration.

After seeing the TV coverage, hundreds of people started showing up to view the spectacle. They signed a petition that Steiner posted at the site, demanding action from NMFS. As the petition pages filled, Steiner faxed them off to NMFS.

“Lo and behold, I got a call back from NMFS and was informed it would take too long to provide the necessary permit, but they would send NMFS personnel to net the fish and move them past the dam,” Steiner recalled. “I immediately issued another media advisory stating that the government was responding positively to the community’s demand for action.”

The next day the media were back to film NMFS personnel standing on the apron, netting the fish and moving them above the dam. But a permanent solution was needed to solve this problem.

Due to all the media attention, many experts as well as hundreds of local community members stepped up to help resolve the situation. A majority wanted to remove the dam to allow unobstructed fish passage, but to do so would be very expensive due to removing all the sediment and/or harmful by sending thousands of tons of fine silt downstream—burying salmon nests below and causing permanent damage to creek habitat.

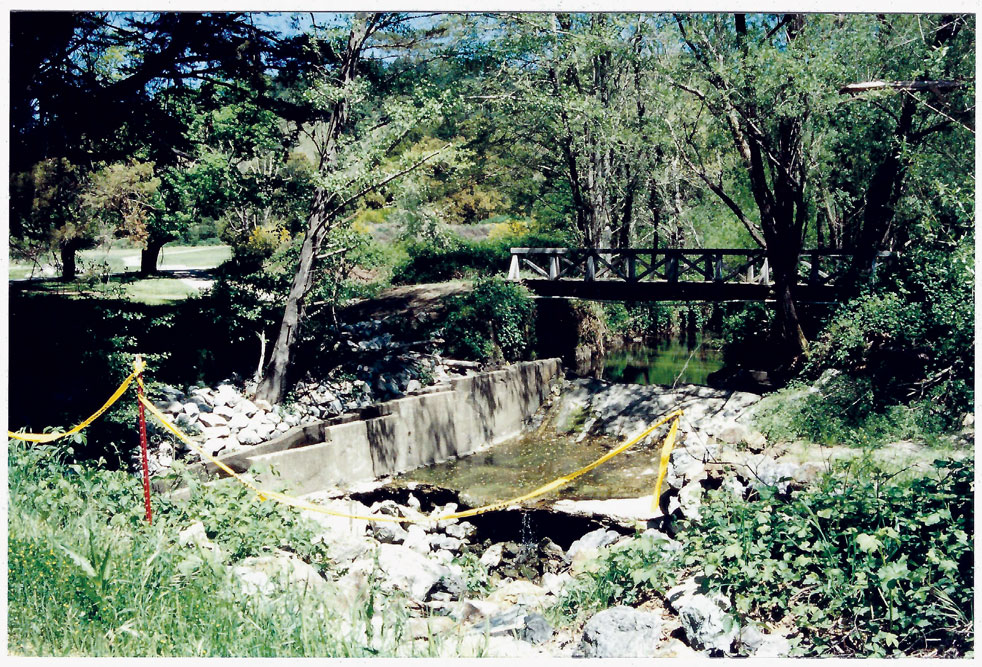

Months of public meetings at the San Geronimo Community Center, combined with field trips to the site, resulted in a plan—Roy’s Pools—to help the fish get past Roy’s Dam. The plan was devised by NMFS engineer John Mann, several private engineers including Woody Trehey and Ed Nute, and input from scores of local community members.

Out of these meetings the idea for a permanent organization to protect and restore the local salmon population germinated, and SPAWN was born. Todd Steiner became executive director.

Roy’s Pools was constructed by slightly lowering the top of the dam and driving a series of metal sheet pilings downstream of the dam to create several deep pools, allowing adult migration over a large elevation in a short distance. Large boulder weir structures—which would normally be a more common and preferred alternative to sheet metal—were not possible due to the large-elevation to short-distance between the dam and the roadway less than 50 feet downstream. In addition, there were limited width constraints of

the creek and the golf fairway.

Once complete, Roy’s Pools looked more like an art installation than a natural streambed, but the sheet-pile pools allowed acrobatic adult coho salmon and steelhead to make the 2- to 3-feet leaps. Unfortunately, due to site constraints, the jump heights proved too big for the juvenile salmonids that were washed downstream as they tried to return to their favored upstream habitat. Even worse, the pools never completely sealed as hoped. This left juveniles and smolts trapped during low spring and summer flow conditions, resulting in the need for annual fish rescue operations by SPAWN and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

It would take another two decades to amass the $2 million needed to engineer, permit, and construct better habitat by ultimately removing the dam and re-creating a natural channel in its place. This restoration project, known as Roy’s Riffles, finally allows salmon and steelhead to swim both upstream and downstream unobstructed by the dam and sheet pile structures.

Completing Roy’s Riffles has been a rough and contentious process. The future of the 157-acre property—recently transitioned from golf course to public open space—has resulted in at least two lawsuits, a county-wide ballot measure, and a new California state law to clarify the need for when environmental review should occur when a government agency contemplates land purchases. Thankfully, the results of these situations landed on the side of better environmental protection.

The first week of the Roy’s Riffles project in August 2020 involved mobilizing giant earth-moving equipment and stockpiling tons of rocks ranging from marble-size gravel to six-ton boulders. Next, the earthmovers began clearing a path and creating a temporary roadway down to the creek. Finally, we were ready to re-route the creek flow around the construction site and to rescue fish in the way of the project. SPAWN could begin taking out the historical dam that symbolized the poor land-use planning of the past century.

In normal times this would have been a celebration with much fanfare to mark the historic event of removing a dam recognized in the Central California Coast Coho Salmon Recovery Plan as the single most important barrier to Central California coho salmon migration. Instead, due to the pandemic, it was a more laid-back affair with a handful of masked friends.

SPAWN’s Watershed Conservation Director Preston Brown (who had shepherded the current project through planning, funding, and permitting and would serve as the day-to-day project manager), SPAWN’s Watershed Biologist Ayano Hayes, and Steiner climbed down into the muddy creek bottom with sledgehammers. They symbolically chipped off the first few pieces of the dam, just as Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt had done nearly 20 years ago when the site was modified with the sheet piles to improve upstream fish migration without actually removing the bulk of the dam.

Bulldozers would roll for the next three months, removing 7,000 tons of fine silt and 85 tons of concrete, installing 850 tons of rocks, and re-creating a meandering creek bed that would need to survive the rushing waters of a 100-year storm at 2,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) and also perform at low summertime drought flows of less than one cfs. Weekly meetings and regular inspections with the contractors, consultants, CDFW, California Water Board, Marin Department of Public Works, and others were daily routines for SPAWN staff.

Volunteers, students, and community members (masked and socially distanced) have helped plant native trees, grasses, shrubs, and other native plants grown in SPAWN’s nursery to revegetate and stabilize the site. In total, 850 trees and stakes; 2,250 shrubs, perennials, and vines; and 3,400 grasses, sedges, and rushes will be planted. In addition, 205 pounds of native grass seed will be broadcast.

Additional work this summer (2021) includes widening the creek and riparian creekside habitat upstream and creating a low-flow side channel to protect juvenile salmonids during large storm events, which will ultimately help create a larger riparian forest. The new habitat will sequester carbon dioxide to mitigate climate change and will improve habitat for land and bird species, as well as support hundreds of species of fish, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians dependent on healthy waterways.

Future work is being contemplated by the new landowners, Trust for Public Land. SPAWN is lobbying for further daylighting the valley floor’s past braided network of ephemeral channels—currently culverted and/or buried under the former fairways—and further laying back creek banks to allow natural flooding during storms into the now buried floodplains, as once occurred before humans altered the landscape for ranches and a golf course. This will give endangered coho salmon a fighting chance at survival and recovery by creating more refuge habitat for juvenile salmon to shelter during high-flow storm events. It will also store fine sediments and filter toxic road runoff, improving creek habitat miles downstream that runs through nearby Samuel P. Taylor State Park and National Parklands.

SPAWN would like to thank all the organizations and individuals who are working on, funding, and supporting this long-awaited project, including the California Department of Fish and Wildlife Fisheries Restoration Grant Program, NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Restoration Center, and the members and volunteers of Turtle Island Restoration Network, SPAWN’s parent organization. Partner organizations and contractors include Environmental Science Associates, Hanford ARC, Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, and Humboldt

State University.

For more information: https://seaturtles.org/our-work/our-programs/salmon/