Racism is an Environmental Issue

By Kerry Reynolds, Southern Humboldt Organic & Regenerative Education

The dramatic events of the past few months—a global pandemic, leading to a global quarantine, followed by an unprecedented uprising of Black Lives Matter protests in all 50 states and across the world calling for an end to racist police brutality—have led me to reflect on how the climate crisis and racism are completely interwoven issues.

The U.S. legacy of slavery and systemic racism has enabled Big Oil to commit legions of environmental crimes and human rights abuses, especially against brown-skinned people in developing nations, while accelerating the climate crisis. We’ll never be able to stop the machine of domination that is rapidly destroying our ecosystems until we acknowledge how our values and actions support and permit it.

Growing Up White in America

Like millions of other middle-class white kids, for most of my life I was naively unaware of the institutional biases of the culture and education system that granted me only the most shallow grasp of the nation’s traumatic history of genocide and slavery.

My first summer job was canvassing for Greenpeace. I was 15, and my mom or dad would drive me 30 minutes to the local Greenpeace outpost in Rochester, New York. From there I would join a merry group of mostly all-white radical working-class bohemians, and we would carpool back out of the (mostly Black) inner city to whatever (mostly white) suburban neighborhood we would be working in, armed with clipboards of campaign handouts. I loved it—every time a door opened I would get a glimpse into a different household, and while some doors quickly shut in my face, often enough I enjoyed engaging discussions about saving whales and dolphins. The discussion that wasn’t engaged, however, was why we were all—at least 95%—white? The Black population lived in the “inner city” of Rochester, and while Greenpeace canvassed there occasionally, we never went during the summers when I worked. Looking back I can see how these unexamined experiences couldn’t help but lead to unconscious associations of whites with environmentalists and suburban homeowners, and Blacks with the inner city that was rundown and ‘dangerous’.

The subject of this strange and uncomfortable racial segregation was never discussed at work or at school. No one ever spoke about why most of the dozen or so Black students that attended my suburban high school were bussed in from the city, and never once did a teacher address the racial history of where we lived. We didn’t read or learn about the tens of thousands of Black people that migrated to Rochester from the South in the 1950s and 1960s, and how none of them could buy or rent a place anywhere except the inner city—which quickly became overcrowded, underfunded, and completely neglected by city government. This story of housing discrimination and segregation repeated itself throughout most, perhaps all, cities in the U.S. We weren’t taught about how 98% of Federal Housing Administration (FHA)-backed home loans went to white people, or how the FHA’s code read, “If a neighborhood is to retain stability it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes.”

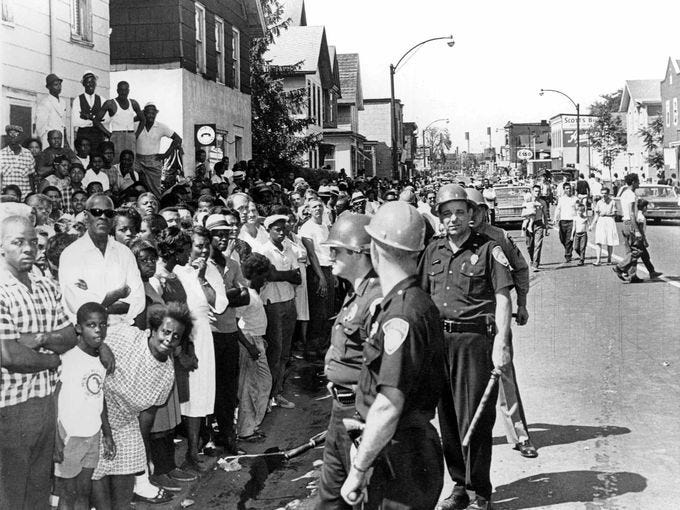

Democrat and Chronicle Staff Photo / JULY, 1964

This pause in business as usual during the pandemic-imposed quarantine is an important chance to grow perspective on our history. I don’t have room here to get into the Southern Strategy, but this political strategy was deployed by both sides of the aisle to exploit the differences between the suburbs and the inner cities—where Blacks were forced to live in overcrowded conditions due to federal housing discrimination. The documentary “13th” skillfully shows how the Southern Strategy led to the outrageous and shameful mass incarceration that makes the U.S. by far the world’s leader in imprisonment.

The Green Insiders’ Club

Let’s consider how environmental organizations might take this time to shake off cultural patterns that reflect an internalized white bias. Look around most any environmental organization and you will likely see a lack of diversity. There is a persistent and significant underrepresentation of BIPOC in U.S. environmental organizations and agencies. BIPOC is a term representing Black, Indigenous, and people of color and you’ll find it commonly used among the new generation of activists with the goals of “undoing Native invisibility and anti-Blackness, dismantling white supremacy, and advancing racial justice,” according to thebipocproject.org.

Green 2.0, an organization that tracks diversity in major environmental groups in the U.S., found that diversity has improved very little since their first study in 2014 concluded that no more than 16% of staff in any organization surveyed were BIPOC, even though BIPOC comprise 36% of the U.S. population and 29% of the U.S. science and engineering workforce.

An environmental leader interviewed anonymously as part of that study said, “I got into the environmental movement back in the 1970s…at that time it was an all-white profession. I was hopeful…they kept talking about diversity. Forty years later…I hear the very same call.”

Meanwhile, a 2019 study by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication concluded that BIPOC are the most concerned about climate change. “Hispanics/Latinos (69%) and African Americans (57%) are more likely to be Alarmed or Concerned about global warming than are Whites (49%). In contrast, Whites are more likely to be Doubtful or Dismissive (27%) than are Hispanics/Latinos (11%) or African Americans (12%).”

The Yale study findings aren’t surprising, since BIPOC are often more exposed and vulnerable to environmental hazards and extreme weather events. Clearly, the success of environmentalism depends upon actively transforming into a broad, multiracial coalition. This includes time and efforts spent within environmental organizations to become more racially literate and question the cultural norms that contribute to our lack of diversity.

“For too long, white environmentalists have ascended to leadership roles because it is generally suggested that they’re more equipped, knowledgeable, and passionate about issues that affect the environment,” wrote Retired Vice Admiral Manson K. Brown, former Deputy Administrator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, in a 2018 opinion piece for The Hill. “This belief is a myth and adversely impacts the progress we have made on a variety of environmental issues. If we want to continue making advancements in the climate change movement, we should be more inclusive and ensure leadership positions are held by a diverse group of experts. This lack of diversity is hurting the movement and stalling progress that’s been made to address the issue of climate change.”

Robin DiAngelo, author of the breakthrough book White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, observes that as a white person you can become the leader of any company or organization in the U.S. without taking a single course in inclusion, diversity, or racial literacy. She also concludes after years of studying sociology that the most racial harm is inflicted on a daily basis by white progressives who do not consider themselves to be racist, yet unknowingly perpetuate racism. She notes that while learning to recognize and interrupt racism can cause white people to feel discomfort, racism is harming and killing people of color every day.

The Whiteness Within Workshop

Southern Humboldt Organic & Regenerative Education (SHORE) is a seedling in the ecosystem of the North Coast’s environmental community—coming under the umbrella of Trees Foundation Fiscal Sponsorship about one year ago. SHORE is committed to nurturing and promoting educational opportunities in rural leadership, healthy land stewardship, and anti-racism.

This August, SHORE will host an online workshop, “The Whiteness Within: Challenging White Supremacy Culture” (see details at the end of article). This four-hour online workshop will span two days and use story sharing, reflection, and physical expression to give participants opportunities to recognize and shift away from racism. White people are the target audience for this workshop, however BIPOC who feel called to observe and/or share their perspective are welcome.

The learning goals of the workshop are to develop a personal understanding of white supremacy cultural norms; to practice and build stamina for self-reflection around issues of racism; and “to recognize how the system of racism shapes our lives, how we uphold that system, and how we might interrupt it.” (Sensoy, Özlem; DiAngelo, Robin, “Reading Guide for White Fragility” 2018)

The workshop presenters are Mo Desir, a Humboldt County artist specializing in Social Justice and Arts Education; Noël August, a Queer performance artist, producer, activist, & educator; and Sarah Peters, a Theatre artist and educator focused on learning in community towards racial justice. Spots are limited, so please register early.

I attended the online workshop in June, and while it was very moving and enlightening, the workshop leaders also made it fun and the time flew by. I hope you can join us in August. Email me at [email protected] with any questions or to join the SHORE email list.

Workshop Details

Dates: August 10 & 11

Times: 3 pm – 5 pm

Where: Online Zoom meeting

To Register: https://tinyurl.com/august10and11

Recommended Reading

White Fragility

by Robin DiAngelo

My Grandmother’s Hands

by Resmaa Menakem

Between the World and Me

by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Me and White Supremacy

by Layla F. Saad

How to Be an Anti-Racist

by Ibram X. Kendi

For more information:

[email protected]